Spider-Man's Living Memory 1: The Death of Gwen Stacy

So uh, the original Gwen Stacy came back.

As a Gwenpool variant.

*ahem*

“Her death is the most heart-wrenching moment in comic book history. Her return will be the most outrageous! Teased last week, prepare for the unthinkable with the resurrection of GWEN STACY! “ … “Gwen Stacy returns as the darker, deadlier, and even more unhinged GWENPOOL, and who better to help Spidey navigate this soul-crushing revelation than the medium-shattering, attention-seeking Marvel Comics superfan that is the original Gwenpool! “ … “ "This is NOT the Gwen you remember. But just who is behind her miraculous resurrection? And what has happened to the original Gwenpool's usually careful existence? Add Kate Bishop and Jeff the Land Shark to the mix and you have the Marvel series of my dreams!"

Marvel.com "Gwen Stacy is Back and She's Here to Slay"

So…hmmmmmmmm, how did we get to here?

For that matter, what even is…

’here’?

Who even is Gwen Stacy? Why does this revival provoke such negative responses?

Well, this blog will get into that, and uh…

much more.

The Gaps In-Between

So, ok, let’s start with some fundamental elements stuff.

-

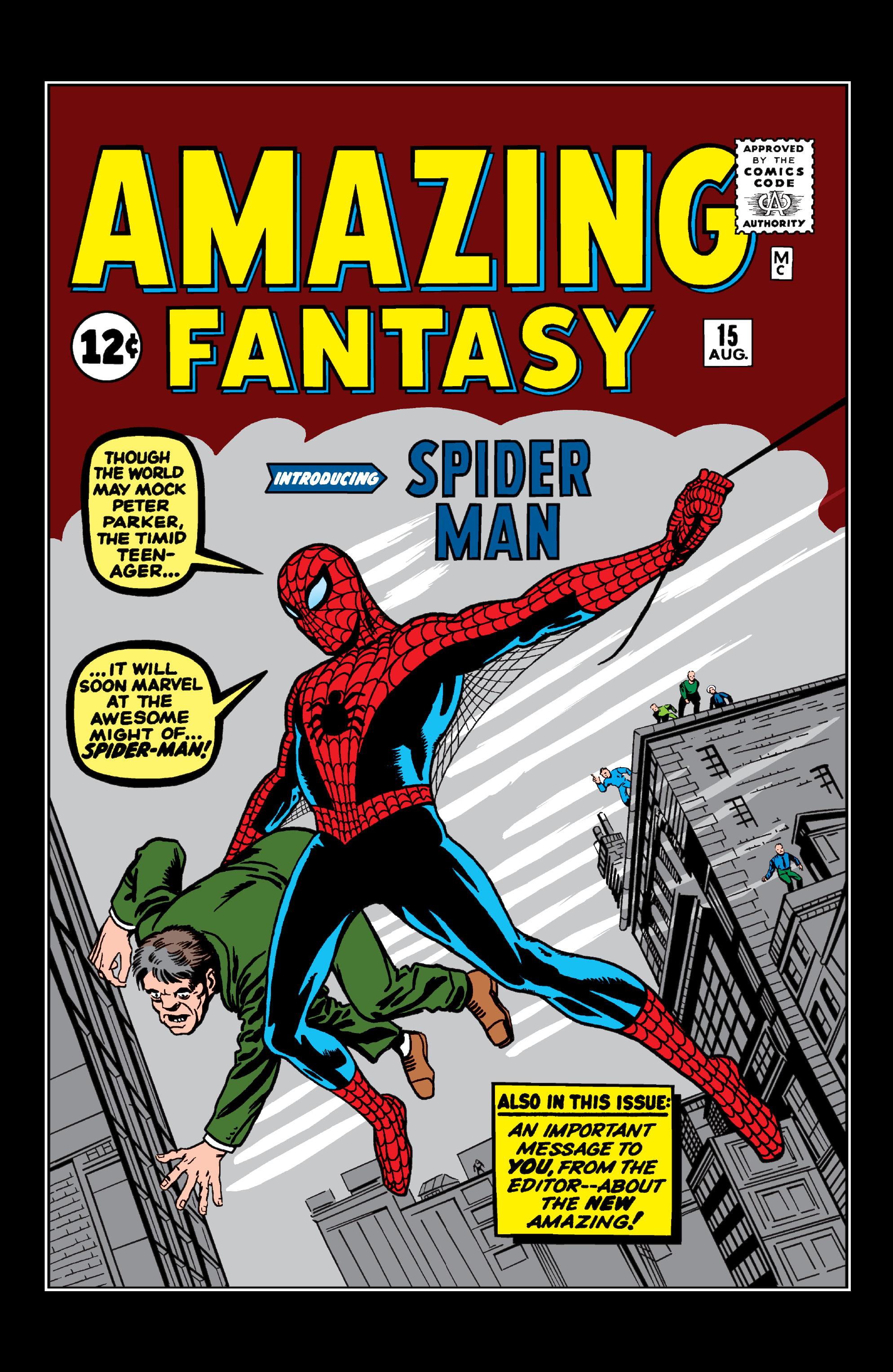

Amazing Fantasy #15 cover image - Spider-Man is a superhero comic book originally created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko in 1962, and is one of the most impactful in terms of reshaping how we talk about and conceptualize the genre next to Chris Claremont’s X-Men. Here is a superhero who needs to deal directly with the environment he exists in rather then being able to fully separate himself due to the gift destiny gave him, a bite from a radioactive spider which gives him powers. If we focus on Peter’s high school days, which only lasted 28 issues, there’s certainly aspects that hold up well such as the origin story and the basic working class vibe of trying to make rent while also having time for school and a social life.

Combined with the nuances of the writing in The Fantastic Four and The Hulk, and it gave Marvel Comics in the early 60s an edge over DC by having characters who were dealing with more relatable struggles to older teens and adults compared to certified Silver Age hijinks. Not to diss Silver Age Hijinks of course, there’s some solid stories in there and goofy is not inherently bad, it just comes at the cost of naturalism, which immediately comes in conflict with an important concept:

closure.

Scott McCloud’s seminal ‘Understanding Comics’ in 1993 breaks down a lot of the basic language and construction of comics, helping to provide an academic perspective on the artform which he felt was sorely lacking in a funny and insightful way, heck I even read this thing when I first started reading Spider-Man comics. It’s a good read on its own you should check out, but for the purposes of this essay I’ll be extracting what he says about ‘closure’, referring to how individual readers construct a whole meaning out of the space between panels, a mental stitch to sew things together by attempting to interpret the given meaning present due to the creators.

This concept can apply to larger and larger scales such as the relation between two pages, two comic book issues, two writing runs, and so on, and the given meaning can be very flexible thanks to how cultural influence makes it easier to interpret icons to have representative content baked into them. So let’s first break down ‘given meaning’.

The interpretation of icons as representations is closely related to surrealist and postmodern philosophy, Scott brings up Magritte’s The Treachery Of Images to show how a representation of a pipe can still carry to meaning of a pipe without literally being one. Even knowing this, however, you are still inclined to see this drawing as a pipe, and also don’t find it odd to have different drawings of the pipe placed next to each other in a sequence. The meaning of the painting is self-evident, but we are still interpreting its implications outside of it.

Now take the cover art of Spider-Man swinging from a web with one arm with someone being held in his other arm, declaring himself as Spider-Man in reaction to the world’s treatment of Peter Parker, his stance bold and confident. Parsing this image requires an understanding of how to interpret lines on paper as representative of different concepts. The word balloons, text, background art, character art, colors, and even what paper the page is printed on are all separate elements of the image that the reader combines together to form a meaning.

Now take that, and juxtapose it with the first page of Peter Parker. We see in the blocking as he’s separated from the crowd, the text describes the scenario, and the artwork reinforces specific emotions, ideas, characters, and concepts in an intricate web of meaning that readers again assemble on their own, and so on and so on.

Thanks to all of this, comic books are able to interweave disconnected moments through the ways that elements are juxtaposed with each other, creating a medium in which both time and space is fractured, with the infinite possibility to interpret and reinterpret events thanks to the space between panels, colloquially known as ‘the gutter’. Thus, as Scott says, ‘comics IS closure!’

I’ll elaborate more on the relevance of the space between panels once we get further into discussing Spider-Man’s story, but for now let’s go back to what I said about a conflict between naturalism and ‘closure’. Peter Parker feels more like a real person then some of the characters who came before, so his everyman qualities therefore conform to naturalism in how he is replicating reality more closely. However, he is in a medium which is packed full of symbolic meaning, which can represent reality but can’t literally be reality. ‘Closure’ is built on things being a story and not reality, and so this tension between ‘real’ and ‘unreal’ qualities is an important, fundamental building block of the character, and it makes it so this first issue is jam packed with deeply meaningful characterization despite ‘only’ being 11 pages.

Amazing Fragments

Now, getting away from the metatextual and into the textual, here’s Pete. He’s a smart nerd with a good home life but a terrible social life. Due to a twist of fate, he gets bitten by a radioactive spider, and from then on has to CHOOSE what to do with this gift.

Peter constructs his identity from the social circumstances he exists in. This not only serves as a solid growing up metaphor, but it also means that how he works as a superhero is malleable and complex.

He only wears a costume in the first place because he wants to hide from potential embarrassment if he fails, which is influenced by how he’s bullied in high school. After taking a risk and having it pay off, it’s only then he creates a flashier costume with webbing to boot, and of course his Uncle Ben dying is what then influences his philosophy and causes him to see things like performance art as a frivolous waste of his gifts in favor of vigilante justice.

It’s not even strictly speaking necessary that Uncle Ben dies for this lesson to taught, but it’s an appropriately shocking and dramatic moment that creates logical cause and effect and makes the story work. He let this guy go, then it came back to bite him, great power yadda yadda.

The point is, like the contrast between naturalism and ‘closure’, growth becomes a fundamental aspect to the character and story as well because of how that concept builds organically taking these ideas to their logical conclusion.

Peter doesn’t immediately become a new person after this, quite a lot of his early stories in fact are motivated by his need to pay rent over pure altruism, contextualized further with how selfless Aunt May is with selling off her jewelry in Issue 1.

To reiterate, Peter being poor like him being responsible is not one of his intrinsic properties the way that his powers are, they are aspects which were developed after his origins. Keep this in mind for much later.

Now, what’s interesting is that Peter’s still very much putting on a performance with his actions here, naively thinking that heroic deeds could lead to fame and fortune only to have that turned on its head. J. Jonah uses Spider-Man as a scapegoat to prop up his son John as a ‘real’ hero, and surprise surprise when he saves him Jonah spins that too.

When he breaks into the Fantastic Four office, he immediately leaves after learning they’re a non-profit and being reminded of his bullying when compared to criminals, which then closes off nicely with the Chameleon using Spider-Man’s bad image for an attempted robbery.

This all highlights the serialization that’s present even this early on, helpfully noted by the editor notes which show up on occasion denoting a callback, although little details such as Peter running out of webbing get addressed more overtly with him being shown to make modifications. These changes from sadsack kid performing for a crowd to misunderstood hero putting up a front against crime are permanent changes that every subsequent story builds upon.

Things from here settle into a bit of a rhythm, with new villains being introduced and subplots with supporting characters progressing in the background. While I’m sure compared to newer comics looking at pages like these feels like reading the dictionary, it does a great job of making each issue feel fleshed out on its own. This was long before it was expected to have always read earlier comics, thus for the most part most comics of this era stand on their own while also contributing to a greater whole.

While this isn’t the time or place to dive fully into the complicated relationship between Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, you check out this incredibly detailed article by Jack Elving if you’re curious, it’s worth noting that a large part of the serialization taking place here can be attributed more to Steve Ditko’s influence and not Stan Lee, although the exact who did what is quite fragmented.

Bare minimum, it is confirmed that Ditko plotted issues 18 and 25 through 38, although due to the nature of the Marvel Method the scripting credit with Stan here is a bit misleading. Stan would typically provide synopses of an issue’s storyline verbally, which would leave it up to his artist to transfer to page. After the art was finished, Stan would then provide the written dialog.

It’s an inherently collaborative process, but due to these credits, which were fairly unusual for the time and did provide some acknowledgment of the work put in by others, and the way in which Stan conducted himself in interviews and with his company, the contributions of his co-creators have historically been minimized by media cycles more focused on a singular auteur rather then grappling with the realities of creation.

To that end, it’s worth noting that along with plotting these issues, Ditko assisted in creating most of the villains, in particular most everything involving Green Goblin including the plotting and earlier unstated foreshadowing, and extended the supporting cast aspect of the story, which for our next discussion includes Betty Brant, with an added page by Ditko at the end of issue 7 confirming Peter and Betty’s growing romantic feelings. Combine this with Liz Allen developing a crush on Spider-Man due to a rescue, and we have the shape of our first love triangle. Well, sort of.

Another history lesson, there’s no test just indulge my tangents, most love triangles in fiction are designed to go on as long as possible due to the presumed infinite well of storyline conflicts that can result from this tension.

The most famous version of this would be the feuds Betty and Veronica have over Archie in Archie comics, Betty typically occupying a 'good girl' role embodying domestic housewife signifiers, and Veronica occupying the 'bad girl' role with a higher social standing and a more brash personality.

These elements are very prone to change over a period of years and decades, but the overall point is to keep the illusion of eternal tension going by having the trio never truly resolving their conflict.

The fact this is never resolved is often cited as the reason why it works. To quote an article by Trevor Van As from howtolovecomics:

"

We’ll probably never get a conclusive answer to Betty or Veronica, but do we really need one? This dynamic has been going strong for 80 years, creating countless stories from it. The fact that it can still get mileage out of it shows that it stands the test of time."

I would argue the opposite, however, first because in the case of Archie part of why it's still continually ongoing is due to how cheap the comics are to produce, and their portability allowing access to markets which regular comic books can't, an issue Christopher Priest has noted in a larger discussion of changes necessary for the comic book industry to thrive.

Second, this seeming eternal conflict is fabricated and could easily be resolved, and indeed it was with a marriage plotline in 2009 in which Archie married Veronica, and then 3 issues later married Betty, with the whole thing very tactically designed to be only a fantasy in the constructed teenage American dream he's ultimately stuck in, with subsequent followups tending to make it very very clear this is an alternate universe or alternate timeline or whatever so you don’t mistakenly stop reading an eternal adolescence….of utena.

I don’t mean to come across entirely disparaging of this dynamic, like at its best its cute fluff which can be comforting, but not delving further into this dynamic leads to two complex characters occupying social boxes that are limiting to their potential.

I keep using terms like ‘presumed’ and ‘illusion’ to describe this dynamic, and that’s ultimately what it is since it’s really not that common in real life to balance between women in such a way that you always have plausible deniability of your intentions, it’s a construction of fiction.

With Betty and Liz, while you can certainly try mapping them as the Spider-Man equivalent of Betty and Veronica,

the problem is their dynamic both with each other and Peter really isn’t that fun or interesting to read about, which is why adaptations of them tend to be radically different or excise them altogether.

Betty starts out interesting with how she supports Peter with Aunt May and doesn’t want him involved with the Enforcers due to loan money she can’t pay back, but then takes a sharp dive once her dumbass brother decides to get in the way of Blackie Gaxton’s bullet and die.

Only 4 issues into a potential relationship, and it’s pretty much permanently quashed, since while Betty doesn’t blame Spider-Man she can’t stand being reminded of her brother’s death whenever she sees him.

With Liz, while she slowly softens over time after seeing Peter act heroic, the fact she's dating Flash at the time and never officially breaks up honestly makes her a bit unsympathetic since this is not really acknowledged as a character flaw of hers, instead serving as fuel for various Flash ter arguments and a lot of jealousy from Betty.

There’s no playfulness in the tension between Betty and Liz, they genuinely seem to despise each other and it mostly makes their arguments over Peter pretty annoying. Perhaps this was intentional, as during this time we get our first teases for Mary Jane, who kind of outclasses both of them in intrigue despite us not knowing what she looks like.

In any case, Betty and Liz ultimately fizzle out as characters and Peter graduates in issue 28, leading us to college life and the introduction of…Gwen Stacy.

"That's When You Had Me, Gwen"

I mean this endearingly, but Early Gwen is a little bit of an unmedicated bitch, like how many characters can you name who compare looking at science experiments to pinups and getting jealous. She bears a lot of similarities with Liz, only implied to be as smart in science as Peter and also well off financially. I honestly genuinely love her attempts to get Peter's attention while he keeps accidentally ignoring her, it's really cute, which slowly builds into a friendship with her, him, and Harry Osborne.

With Ditko off the title after Issue 38 and the introduction of John Romita Sr., two major revelations happen. First, Norman Osborne, Harry's dad, is revealed as the Green Goblin and suffers amnesia once learning Peter's secret identity. This is the first time a villain is tied to Peter personally rather then just thematically, and creates a looming threat that might reappear at any time.

The second revelation is the true introduction of Mary Jane Watson.

What makes MJ immediately interesting compared to other love interests is her personality. She's an easygoing partier who appears to not take things too seriously, using a lot of slang which might be dated now but felt relevant and hip then. Her first lines are simultaneously teasing and sincere. She doesn't fully think Peter is a tiger, but she appears self-assured enough to already be joking around and teasing since she knows the effect she has on people.

When their date gets interrupted with superhero shenanigans, she’s willing to go see Rhino with Peter without him needing to come up with an excuse, along with working a steady job at the local cafe. This contrasts her perfectly with the more upper class and book-smart Gwen, so naturally you would think that this would be the Betty and Veronica dynamic the comic was looking for, but as it turns out this once again isn’t the case.

Let’s now bring up a point Howard Mackie, a later writer for Spider-Man, made in an interview, specifically how he considers Gwen, Peter, and MJ as a perfect triangle, and thinks that things started going astray for the comic once Gwen died.

Without familiarity with the material this seems fine, but upon examination of both behind the scenes information and close reads this doesn’t have as much weight as you’d think.

In a few interviews, Stan Lee notes how he and Romita Sr. wanted Gwen to be the heroine of the book over Mary Jane, citing Gwen as more serious and caring over the fun-loving hippie-type MJ was cast as initially, and only introduced her just for some fun. This is despite the fact that there is significantly more buildup in the narrative for Mary Jane’s appearance compared to Gwen’s, which I’m visualizing onscreen with notes on every time MJ is either mentioned or shows up before #42 in contrast to Gwen. As you can see, present from much earlier on.

Even comparing the first panels they’re both fully onscreen clearly gives Mary Jane a much greater focus in addition to being the cliffhanger for the next issue as opposed to midway through #31 in a crowd shot with Gwen. So what gives?

Well, according to Romita Sr., we have confirmation that Stan had deliberately delayed revealing Mary Jane properly due to disagreements with how Ditko was handling her, and indeed before Issue 42 MJ does act quite a bit different despite us not seeing her face, even driving off in a car that never appears again in Issue 38, the last issue Ditko worked on.

Thus, we can validly read MJ’s treatment in the story as a combination of two contrasting intentions which serves to present someone who exceeds both. I think it was the right call to have MJ act the way she does rather then more high class and proper, even if the intention on Lee’s part was to defocus her for the more serious Gwen.

In any case, if it’s true that we’re supposed to read the Peter/Gwen/MJ dynamic as a fully fleshed out love triangle, then it’s strange how Gwen’s personality radically shifts after MJ’s introduction, no longer having the same sarcastic edge or focus on science and instead also becoming much more fun-loving and hip.

Take how she acts during the party she set up in Issue 47, where she sees MJ making a play for Peter and goes to town on the dance floor, or Issue 48 where she tries wearing her hair more like MJ, something that even gets commented on. This shows she has an understandable level of insecurity around MJ, worrying that she might no longer feel seen if she’s around.

The very next issue, she shows up to cheer up Peter and is suddenly all smiles, with the animosity towards MJ being reduced to cute, smooth banter. Her artwork even changes, no longer having a distinctive face like with Ditko and instead at times looking identical to MJ.

This jump in how she acts is very pointed, and indeed when looking at interviews both Romita Sr. and Stan confirm these changes were done in order to try to get the audience to favor Gwen, since even at the time the audience preferred MJ. (get sources)

Subsequently, this answers why Peter and Gwen somewhat abruptly start their relationship in Issue 59, and MJ disappears for 15 issues between 66 and 81.

What makes this more interesting is despite the attempt to sideline MJ, the writing seemingly by accident does a much better job setting her up as a more dynamic character. If we examine Issue 59, while Gwen and her dad are involved in the plot the dramatic thrust is focused on MJ, seeing as how she gets roped into a villain’s scheme while trying to work a job, and ends up getting a romantic heroic rescue by Spider-Man.

In the next issues, she tries to warn Captain Stacy about what happened, and is shown having concern over not being paid for her job. While mostly played for some laughs, this again shows her as a working class girl who gets involved with superhero shenanigans, and very much mirrors some of the struggles Peter also goes through.

Contrast this with Gwen’s role, with her mostly reacting to her father being mind controlled and a misunderstanding over him trying to attack Peter which leads to them not speaking to each other for a long time.

While Gwen is also subject to a dramatic rescue in Issue 61, it involves her specifically as a character far less seeing as how she’s just going along with her controlled father, and the the resolution of the story focuses on both of them being rescued along with a heroic gesture from Norman Osborn.

Thus this again leads to a situation where Mary Jane feels like a more organic component of the narrative, with Gwen’s involvement feeling almost perfunctory despite the intention being her as the main girl.

This greatly calls into question the legitimacy of Mackie’s claim about the love triangle being a central component to the story, especially when you consider that MJ’s 15 issue disappearance coincides directly with Peter and Gwen making up.

Now, I’m not saying that Gwen and MJ actually needed to be continually framed as opposites ala Betty and Veronica, its just that Gwen and MJ only truly form this triangle in a metatextual sense, in the actual stories which involve both of them you can see a rather haphazard handling where Gwen’s character traits and relationship with Peter rapidly fluctuate while MJ stays relatively consistent. This doesn’t read like a Betty and Veronica love triangle, this reads like the writers favoring one character over another to the detriment of a more fun dynamic.

This ultimately places Gwen in a very awkward position where her more interesting character traits are sanded off in service to the Superhero Girlfriend mold of constantly worrying about her boyfriend, and most story beats during this time focus on her dad rather then her as a character. Despite implications that she’s supposed to be Peter’s intellectual equal, she can’t figure out he’s Spider-Man and rarely if ever contributes to plotlines which would involve her knowledge in science. There is no synergy between any of the established elements with Gwen, and it leads to a dynamic with Peter that feels confused and shallow.

We can further highlight this missed potential with some smaller moments in which she breaks from this mold.

During the Lifeline Tablet saga, her and Peter attend a protest to try to convert the exhibition hall into a low-rent dorm for students who are financially struggling. Since Peter dips out for superhero-ing, she’s put in a position where she needs to defend him from the accusation that he’s a coward. This causes an argument about where Peter stands on student rights, which is dramatically ironic since as Spider-Man his stance is pretty clear.

In Issue 82, Peter opens up to Gwen for the first time about his financial troubles, and they have a pretty real conversation, with Gwen’s support motivating him to try and make things better.

Both these moments have a through-line of financial burden, which implies a class disparity between Peter and Gwen which could’ve potentially been very interesting to explore, but sadly these remain just moments, with subsequent storylines not really following up on these details, or providing simple solutions that don’t involve Gwen at all, and contributes to a status quo that is frustratingly static despite the real-life context of the time providing ample opportunity outside of this for more complex storytelling.

Captain And The Ship

It’s how you go from ‘Spider-Man No More’ and the introduction of Hobie Brown to underbaked b-plots like Gwen asking Flash if he knows Peter’s secret and oops now Peter thinks Gwen is cheating on him because they’re terrible at communicating, like wow truly riveting stuff. They don’t even resolve it directly by, you know, opening their flaps and talking about it, Flash has to be the one to tell Peter like what the hell.

What exacerbates this problem is Captain Stacy who serves as a Commissioner Gordon type, someone associated with law enforcement willing to work with Spider-Man and put in the good word. He has major suspicions of Peter’s secret identity, but only alludes to them rather then outright accusing. He also acts as a father figure for him, something Peter’s been missing since the death of Uncle Ben.

This makes him a pretty complex and multi-faceted character, and I certainly like his writing a lot more then Gwen’s sadly, but as I implied he’s part of a status quo that feels a bit convenient, since it seems like all Peter needs to do to live the good life is stay with Gwen, tell her his secret, and boom no more money problems or issues with the police. This would alter what the story at its core is about, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but was certainly something Stan Lee was opposed to changing at this point in time.

To that end, before we get to the one storyline original Gwen Stacy is known for, I think it's important to examine the death of her father. This is often treated as a footnote when discussing the story, something to the effect of 'after Captain Stacy died, then Gwen died', which is understandable since Gwen’s death very much superseded this in terms of textual and metatextual importance.

However, I still think it’s worth focusing on Captain Stacy’s death first, since the way in which it was handled and the fallout of it in part laid the seeds for the justifications as to why Gwen’s death was written, something that I often feel is under-discussed academically.

That being said, what makes this difficult is there is no interview or source I could find from anyone involved detailing exactly why the decision was made to kill Captain Stacy in particular. From what I could scrape together, his death was a calculated story decision, but the planned fallout of it is murkier.

Thanks to the letter the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare sent to Stan Lee on October 8, 1970 to create a storyline promoting an anti-drug message, we have a rough timeline we can use to help speculate on what the intentions were for this.

Ok, so, Issues 88-90 detail the storyline where Captain Stacy died, issue 92 came out 5 days after this letter, and issues 96-98 are the 'drug trilogy' dealing with Harry's issues with mental health and the return of the Green Goblin. Incidentally, this was a landmark storyline which defied rules stipulated in the Comics Code Authority and was released without it's approval.

Issue 96 came out in February 1971, which tracks with professional comic books roughly taking 2-3 months to produce, so we can assume planning for the storyline was underway as soon as Stan read this letter.

While it's reasonable to suspect the return of the Green Goblin was planned after the dubiously canon first version of Spectacular Spider-Man failed to take off, the murkiness comes from whether his return was always intended to be directly after Captain Stacy died, or it came about from the process of writing the anti-drug storyline.

Personally, I think it's the former and I'll be basing my analysis on that, but just know this is only based on close readings of the text, and could be contradicted once new information comes to light.

Now, let’s start things off with issue 87, which features a delirious Peter convinced he’s losing his powers. This comes after several issues with him failing to sleep and being physically and mentally exhausted, which leads to him almost stealing pearls for Gwen and revealing himself as Spider-Man. This all gets wrapped up neat and tidy with the explanation that he just had the flu and some assistance from Hobie, but as a prelude to what’s to come there’s some interesting implications.

The reason Peter tries to steal the pearls besides his delirium is because he genuinely can’t afford any nice gifts for her birthday. Considering that he’s only able to afford rent thanks to Spider-Man, and it’s understandable he’d become desperate when he feels he’s losing his only blanket for financial stability. This sadly doesn’t materialize at all in the scenes with Gwen later, but hey still neat.

With revealing himself as Spider-Man, we can note the supporting cast’s reactions, particularly with having future context with Mary Jane and Captain Stacy. Mary Jane while initially shocked quickly turns everything into a joke, while Captain Stacy frames everything more logically and helps paper over some of the holes in Peter’s story.

Considering his earlier behavior, I imagine he put together Peter was Spider-Man after saving Gwen from a car crash and dipping, and wanted to have Peter confide in Gwen in an honest way rather then him being the one to tell her.

Captain Stacy’s death takes place directly after this. Due to some events involving Doc Ock hijacking a plane for ransom, yeah it was the 70s, he’s on the run causing a great deal of destruction, including threatening to take out an entire power grid just to lure out Spider-Man. Due to how strong the tentacles are, Peter comes up with a special web fluid to short out his ability to command them. This causes Ock’s tentacles to start attacking him, which accidentally causes some rubble to fall to the road down below. Seeing the fight, Captain Stacy dives in the way to save a young boy at the cost of his own life.

As a quick sidebar, Doc Ock did not kill Captain Stacy, contrary to what you might be led to believe reading some posts about it online. He fully did not have control of his tentacles and even if he did it’s very unlikely he would let the people below die without some ulterior motive like forcing Peter to save them or something.

This misinterpretation stems from later retellings assigning blame to Doc Ock, most prominent in issues 181 and 365, with the example in 365 being the most egregious since Stan Lee also wrote that story, which makes me suspect he didn’t re-read to keep it consistent.

It’s also not Peter’s fault Captain Stacy dies although as is typical he blames himself anyway, he had no way of predicting the chimney would get knocked over and didn’t have the ability to get Ock into a less dangerous place to fight since he was taken by surprise. The fact of the matter is this is fully a tragic accident in which neither party involved in the fight intended, which adds an interesting layer of reality to the otherwise routine superhero stuff.

Sidebar done, with his dying words Captain Stacy confirms he knows Peter’s identity and gives his blessing to take care of Gwen in his place. This provides a complex layer of catharsis, since while it shows Peter would be accepted by the people close to him if he did trust them with his secret, the revelation comes with a death that puts a permanent wedge between him and Gwen.

Or, well, it SHOULD’VE put a permanent wedge, but unfortunately the follow-through is messy and frustrating.

Now, I actually like this story with Bullit, it's a good look at fear mongering and the exploitation of grief, but you can see how once again something specific to Gwen’s character is used as a jumping off point for an otherwise unrelated storyline. Her hatred for Spider-Man festers entirely due to Peter once again choosing not to communicate with her, and an issue which could’ve had Peter actually tell her his identity gets devoted to a fight with Hobie, and so on and so forth.

The needed progression with Peter and Gwen should be a conversation between them about his identity, but since the underlying logic of the story bars that we’re instead treated to a series of pretty overt contrivances and coincidences to force them apart for long enough that we forget that Peter was fully committed to tell Gwen his identity.

This is most frustrating with Issue 95, where Peter goes all the way to London to talk to Gwen but gets wrapped up in a random terrorist plot and exposes that Spider-Man is there. Now, despite the entire reason he’s here in the first place is to talk to Gwen, apparently he changed his mind about revealing his identity to her and he just goes home right after. He even has the audacity to get upset over the idea of Gwen not writing him, like bro you’ve done literally nothing to fix this relationship and you’re upset about that??

Even worse, when Gwen returns at the end of the ‘drug trilogy’, there is literally no point where Peter sits down with her and has a conversation about her father’s death. Apparently, all that was required to fix the relationship was to have GWEN realize she was wrong with no further input necessary from Peter.

Like damn this boy would rather try to get rid of his powers and grow six arms rather then tell her the truth, it’s crazy!

While the actual ‘drug trilogy’ is mostly written fine, ignoring the inaccuracies with its depictions of drug use, as is becoming a running them I can’t help but feel there’s quite a lot of missed potential here. Thematically, the Goblin’s return provides an interesting contrast to Captain Stacy’s death, since Norman’s neglect and abuse of Harry led him to develop terrible coping mechanisms while Gwen is overall well-adjusted and able to carry on after tragedy. When you consider the death of Uncle Ben is what led Peter to be Spider-Man in a more responsible way, and future context with Mary Jane as is implied here, and you have a story about four adults all dealing with the shadows of their fathers.

However, since Gwen is still treated like a plot device and Mary Jane despite being given killer lines is mostly on the sidelines, this potentially deep story ends up feeling like a surface level exploration.

Obviously if I had it my way every comic would read like a Chris Claremont with constant interior monologues on perspective and emotions and all that, but you can see what I’m getting at, and indeed later works like Shadow of the Green Goblin and Parallel Lives do exactly what I say and interlace all of these character’s lives and the effects their parents had on them in complex ways. Most of the best writing original Gwen received was made decades after she died, it’s super frustrating.

The story we got back here in the 70s ends up being a ripple that fades away, with Gwen and Peter back together and the drama resetting from dealing with grief to the endless circling of keeping the secret identity hidden oh joy.

The last few Stan Lee scripts along with the Roy Thomas fill-ins feel rather subpar as a result. There’s some interesting bits like the origin of Morbius and a critique of the Vietnam War once you trudge through some orientalism, but then you get a scene like where Gwen yells at Aunt May for babying Peter during a time that neither of them have any idea where he is after he got kidnapped.

This frustration was reflected in the letters from fans at the time, including a particularly critical one from Tom that points out how much the plotting has become cyclical, with the fallout of Captain Stacy dying mirroring the fallout with Bennett. It’s the kind of letter you would expect nowadays, but it shows that even all the way back in 1971 readers were very much wanting more growth and change in the story and characters rather then a reliance on an endless status quo.

It helps, then, that for better or worse, the cycle is about to break.

Memories Of Death

Enter Gerry Conway, who took over for Lee in writing duties at the ripe old age of 20.

As someone much closer in age to Peter, this gave him an interesting perspective on the character and his direction, which perhaps isn’t immediately obvious with his first 10 issues needing to resolve plot threads left behind by Stan, including a retooled incorporation of an issue of the Spectacular Spider-Man magazine for #116-118. While not bad issues by any stretch, by design they were meant to adhere to the status quo that was already established and didn’t do much to reinvent the wheel.

This all changes with issues 121 and 122, the...day Gwen Stacy died at the hands of the Green Goblin and Norman's subsequent karmic death.

Now, it's easy to fall into the trap of overly mythologizing the importance of these issues, particularly noting the common interpretation that Stan Lee had no involvement in creating this storyline as incorrectly reported in various articles.

As sourced from other interviews from then-editor in chief Roy Thomas, John Romita Sr., and Gerry Conway himself, they seeked approval from Stan on the subject and got it. I don’t want to say Stan was exactly lying with his claims of not really knowing what he was agreeing to since it’s likely he was focused on other responsibilities, but this shifting of blame onto decisions made by his younger staff is very strange considering he was both the president and publisher at the time, and thus had authority over what got published or not. If he genuinely didn’t approve of Gwen being killed, then the story simply wouldn’t have seen the light of day.

More then likely, this came about due to very harsh criticism he received from fans after the issue came out, and wanting to save face perhaps inadvertently put the pressure on Conway instead, which led to him not being able to go to conventions for a very long time.

That being said, it is true that Romita Sr. and Conway were the people who initially planned the death, or at the very least made manifest ruminations going on in the Bullpen. For Conway, he viewed Gwen as a poorly written love interest whose focus came off confusing in comparison to the more potentially dynamic and interesting Mary Jane. In more recent interviews (ASM2 stuff) Conway has further clarified that he regrets the trend of killing off love interests this inspired, and wouldn't have chosen to kill Gwen if she was more like Emma Stone's portrayal in the Amazing Spider-Man films.

So why exactly was a death planned the way it was in general outside of Conway’s intention? Well, I suspect the choice was made as a way to de-age Peter, reinforced thanks to an editorial comment that there was nowhere else to take the relationship with Gwen except towards marriage, which would mean fundamentally altering an aspect of the main character that had to be committed to. This indicates a marriage was never really in the cards, and so an honestly pretty cynical out was created with Gwen’s death to change the status quo not unlike what happened with her father before.

This is pretty strange from a character and story perspective since if the characters had like one real conversation about this I’m sure it’d be fine, but that doesn’t sell books so the most extreme it is.

While we’re de-mythologizing, it’s important to also note that Gwen’s death was not the end of the Silver Age. This perception sprung up due to the excellent Marvels miniseries in 1994, when in reality the Bronze Age begun at the very least in 1970 due to the landmark Green Lantern/Green Arrow series, which took a relatively grounded approach and attempted with some success to discuss complex, mature topics that comic books normally shied away from. If we pull just from Amazing Spider-Man, then you could argue the drug trilogy was the turn or even earlier with the introduction of Hobie Brown as a supporting character. Point being, comics did not grow up with Gwen Stacy's death, they been growing.

Anyway, let's stop the metatextual and get to the textual. After fighting the Hulk in Canada, I guess an inauguration before major events, Peter is under the weather with a cold, and comes back to New York to Harry back on drugs. This causes great concern for all of his friends, and due to this and the stress from work Norman once again snaps and remembers his Green Goblin identity, kidnapping Gwen and threatening to kill her on a bridge. During the scuffle, Gwen is knocked over the edge and Peter desperately tries to save her with a web line, only to realize after pulling her up that she's dead.

Unfortunately although not unexpectedly, very little of Gwen's final story is actually about her, the most she gets is some concerns over her friend Harry, and even that serves as setup for Norman's evil, with her dying without so much as knowing Peter is Spider-Man. There is a complete lack of resolution or emotional catharsis to her death unlike with her father, which is very much the point but is very sad to see done to a character who had unlimited choices in directions to go.

Indeed, the most complex part of Gwen's character ends up being the nature in which she died, since while it's stated by Green Goblin that the shock of the fall killed her, quite a lot of analysis from critics and later interpretations by other writers argue that instead the whiplash of Peter's webbing snapped her neck. The same editorial comment from Roy Thomas I brought up earlier even confirms from his perspective that the web killed her, while also noting that regardless Peter wouldn't have been able to do anything to save her due to the speed in which she was falling.

The text as written supports the Goblin's assertion that Gwen did die from the shock of the fall, like he isn’t lying here or something that wouldn’t make sense for his character.

While it’s certainly a very weird way to go, it’s not outside of what’s been established before to soften deaths that would otherwise come across more brutal, hence why we never see Uncle Ben’s death or blood in general. The way violence is coded during this time is always to partially abstract it so as to not upset younger readers, the 90s this ain’t.

Of course, this snap sound effect being present at all is suspect, and worth keeping in mind it was added during the inking process and was not something which was in the original outline. If we want to talk from a perspective of pure authorial intent, while Conway did add the snap for unconscious reasons to fit an action, in all later references he makes to this event it is always stated that the fall killed Gwen and not the snap.

To be thorough, I even went ahead and tracked every reference I could find to her death up to 2005, and with the notable exception of Marvels the only time the snap is visibly shown and not implied is Sins Past, which is certainly…something…look we’ll get into it later.

Point being, later references tend to favor focusing on the snap and not the fall, which while much more logical a way to go is bumping into what the story of Gwen’s death actually is. Peter failing to save Gwen in this moment due to a cold and the Green Goblin’s interference does not therefore mean that he murdered Gwen, since if he genuinely felt that way he never would’ve shouted about how the Goblin killed her.

He has complex guilt over this event and blames his role as Spider-Man as contributing, but to say he himself killed her is overly simplistic.

While you can certainly argue that Peter letting Norman run around at all was a major problem due to the potential danger he poses for everyone, you can at least justify that reasoning thanks to the fact that Norman did actually help save both Gwen and Captain Stacy in Issue 61, and his reversion to amnesia later on was spurred by the worry he felt for his son suffering from a drug overdose. Within the context of this story, there is no reason for Peter to immediately assume Norman is a threat to anyone when he's in a similar situation of taking care of his son, along with Peter not being privy to the knowledge of the stress Norman’s under with his company that we as an audience have. That’s what make things so dramatically ironic, we see the pieces put in place that led to things happening this way but the characters in the story have no idea.

More then anything, what’s meaningful about this story has to do with the fallout of the event rather then the event itself, and even with all my reservations I can’t deny how powerfully effective Conway’s writing here is.

In The Goblin’s Last Stand, Peter is alarmingly haunted and angry, lashing out at those close to him and making the situation worse for himself, which is very understandable considering how much Gwen’s death hurts him to his core.

There’s an emotional intensity here that feels quite unlike anything we’ve seen before, it gives everything this ineffable realness that sharply conforms to naturalism for the first time in ages. It’s no wonder folks tend to read Gwen’s death as another Uncle Ben moment, the feelings you get reading it very much mirror the mood of that first original story.

The eventual fight between the Goblin and Spider is very intense, with Peter almost going over the edge and killing him before stopping himself short. In yet another ironic twist, Norman’s attempt to kill Peter results in his own death, forever limiting his choices down to this sad, pathetic end.

With it, the final theme of the story presents itself: the absence of meaning in the face of death. Peter got his revenge, but it doesn’t change the hole that is now forever in his life with Gwen gone, or the consequences he’ll have to face from treating the people around him so harshly.

What transforms this story from great to revolutionary is the epilogue, with Mary Jane waiting for someone to come home to try to grieve and help understand what has happened.

Peter pushes back at the idea of MJ being torn up, understandably since before this she was never there during difficult or tragic moments, making jokes and not taking anything seriously.

In what I would argue are the three most important panels of the entire canon of Spider-Man, Mary Jane starts to leave the room, but after hesitating in the doorframe instead chooses to slam it shut and stay with Peter in his grief.

This along with the Goblin’s death were actually redrawn by John Romita over Gil Kane’s pencils, with Conway wanting a more quiet desperation and kindness from MJ, which I definitely feel was the right call since while she is indeed being very kind and wanting to comfort Peter, the focus of the scene is entirely on Mary Jane’s interiority and perspective.

We are seeing for the very first time how MJ is not just a frivolous party girl playing with men’s hearts for her own amusement, but a scared lonely girl unable to find her place in the world, always running off when things get tough to protect herself. Between these panels, we are forming the closure necessary to understand the reality that had been hidden away from us, and put together along with Mary Jane who she is as a person. Just as Peter made the choice to help others, so too does Mary Jane.

So it just leaves a question.

Who IS Mary Jane?

Sources

https://elvingsmusings.wordpress.com/2021/10/12/serialized-ditko-the-green-goblin-mystery/

https://elvingsmusings.wordpress.com/2022/04/03/people-who-died-character-deaths-between-af15-to-asm122/

https://www.twomorrows.com/alterego/articles/09romita.html

https://comicbookhistorians.com/the-ditko-version-exploring-steve-ditkos-recollections-of-marvel-in-the-1960s-by-rosco-m-copyright-rosco-m-2023

http://www.rcharvey.com/hindsight/ditkoleespiderman.html

https://www.howtolovecomics.com/2021/02/14/archie-love-triangle

https://www.cbr.com/archie-comics-archie-marries-veronica-betty

https://www.spidermancrawlspace.com/interviews/mackie4.htm

https://twomorrows.com/comicbookartist/articles/06romita.html

https://www.twomorrows.com/alterego/articles/09romita.html

https://cbldf.org/2012/07/tales-from-the-code-spidey-fights-drugs-and-the-comics-code-authority

Marvel Age #54 page 13

Alter Ego #104 page 30

Marvel Comics: The Untold Story

https://scarysarah.medium.com/a-brief-and-broad-history-of-post-golden-age-pre-digital-comic-book-coloring-9fe9e386149a

https://forums.superherohype.com/threads/what-about-captain-george-stacy.342887

https://www.reddit.com/r/Spiderman/comments/mwwuvg/spidermans_archenemy_osborn_or_octavius/

https://www.reddit.com/r/Spiderman/comments/1689a8y/unpopular_opiniondoc_ock_is_spidermans_true/

https://vocal.media/geeks/there-s-no-spider-man-without-gwen-stacy-revisiting-the-death-that-changed-marvel-comics-forever

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSJWm2yM2yk

https://screenrant.com/spider-man-gwen-stacy-death-physics-kakalios-goblin/

https://www.cbr.com/john-romita-sr-reflects-on-his-spider-man-legacy-gwen-stacys-death-and-stan-lee/